Calke Abbey in Derbyshire is not a place that simply exists in the present. It lingers—quietly, stubbornly—in the past. Once the bustling country seat of a wealthy English family, it now feels suspended in a state of arrested decay. The National Trust, which now manages the estate, made a conscious decision not to restore the house to its former grandeur but instead to preserve it *as found*. The result is a house that feels oddly intimate and startlingly real—frozen in time, gently fraying at the edges, and whispering stories of decline and disuse.

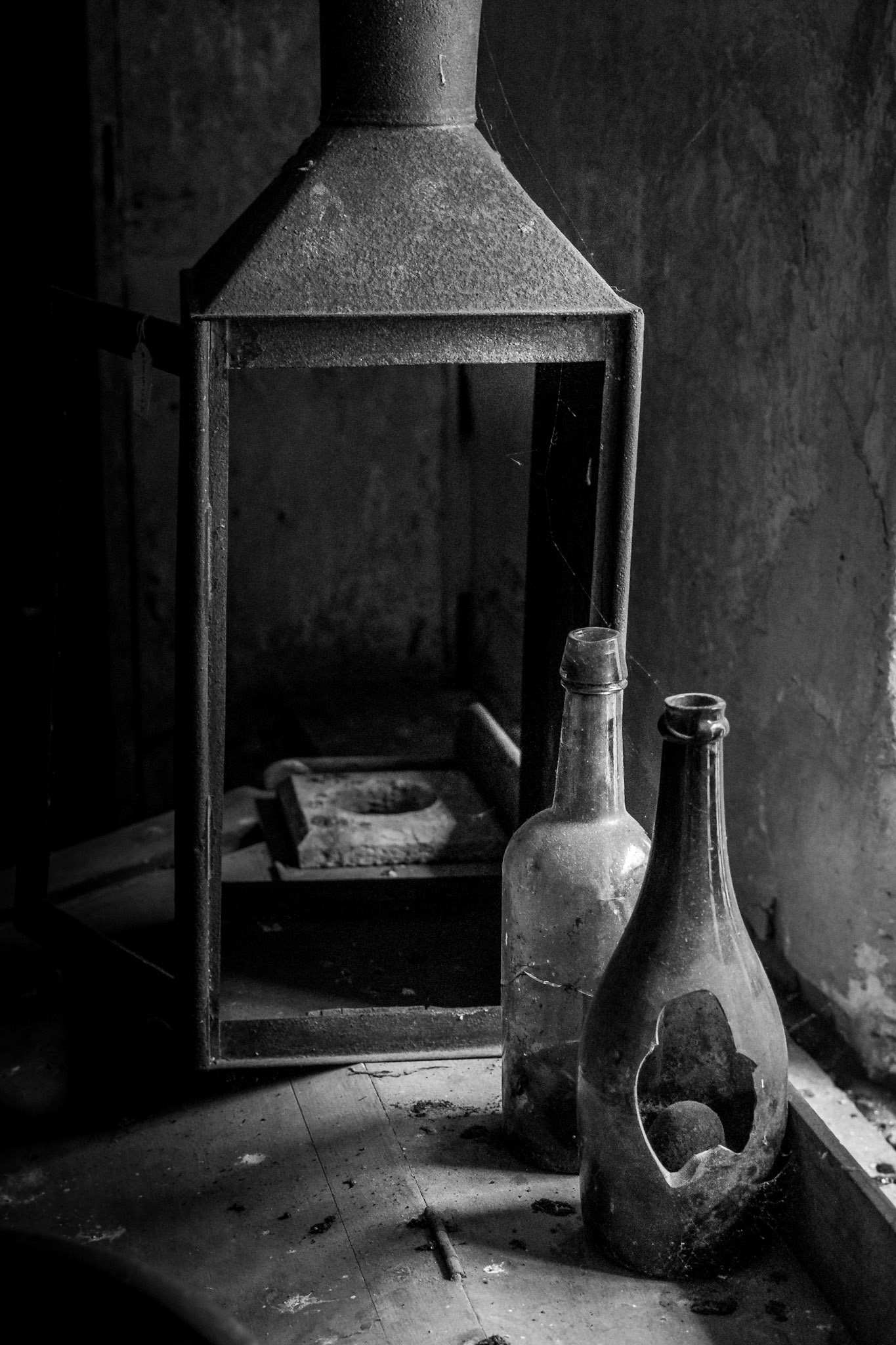

From the moment you step inside, there's a palpable shift in atmosphere. Downstairs, rooms retain a sense of order—perhaps an echo of the formality and social life that once defined them. But as you move upwards through the house, that sense slowly unravels. The ground floor gives way to the upper levels where dust gathers thickly on forgotten surfaces, and light fights to break through heavy shutters and drawn curtains. Here, in the half-light, the house seems to exhale. You’re not just visiting a stately home—you’re stepping into the memory of one.

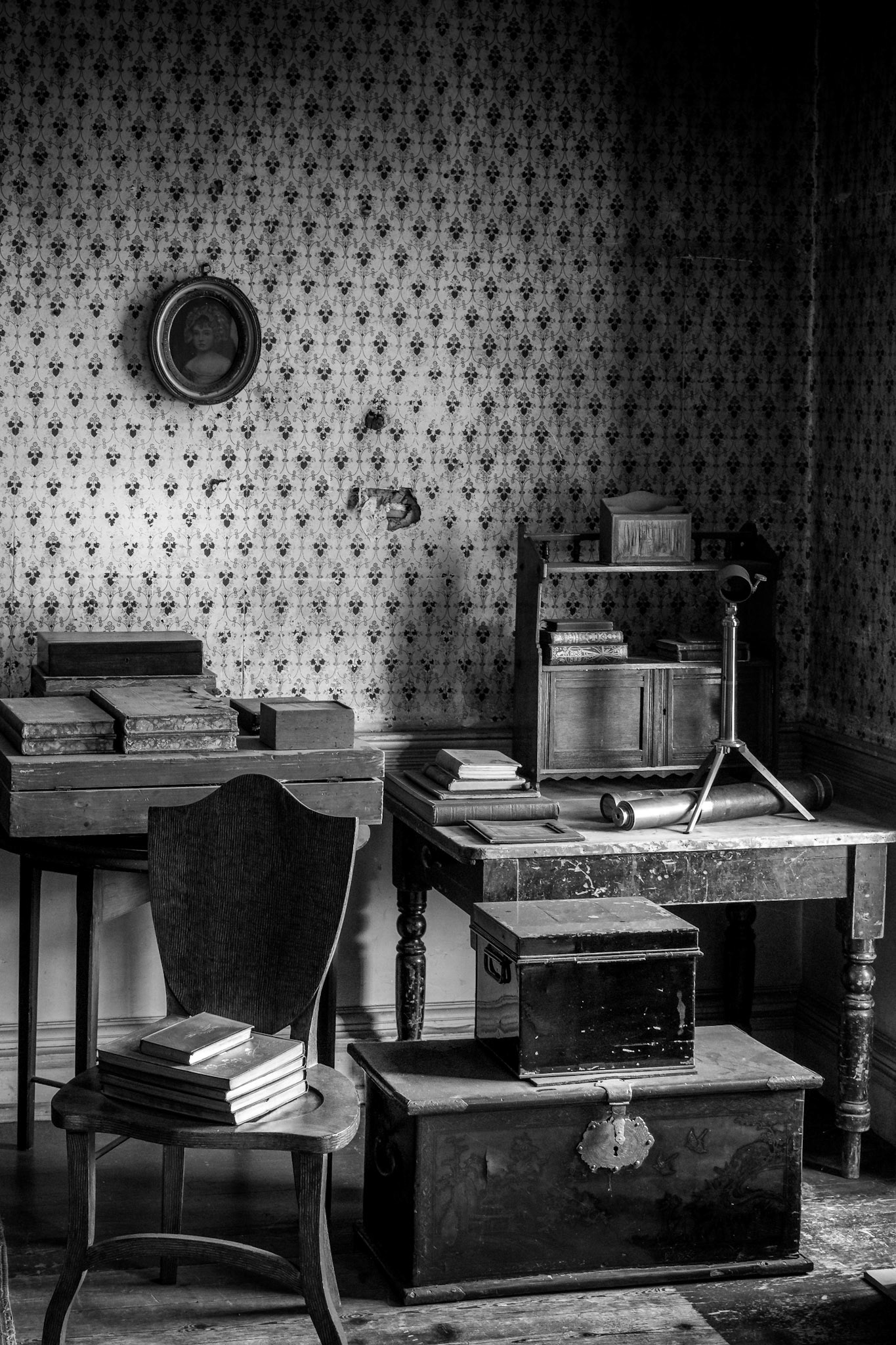

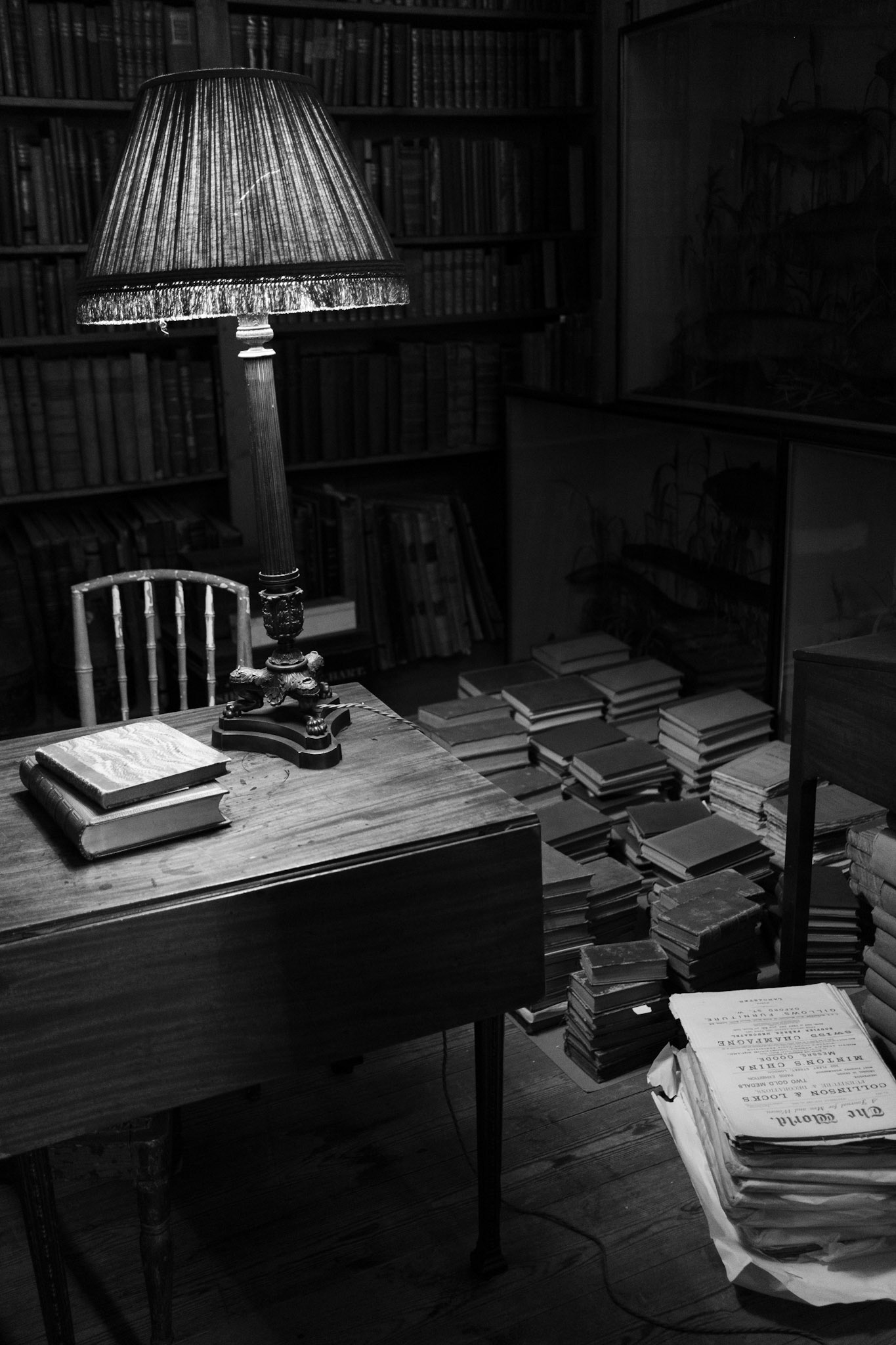

Photographically, Calke Abbey is a gift. It doesn’t demand grand, sweeping shots of architecture or landscaped gardens—though those exist. Instead, it invites attention to the details: a shaft of light catching the worn edge of a table, wallpaper peeling back to reveal older layers beneath, a lone chair positioned as though someone has only just stepped away. Every corner, every object, holds the potential for an image that tells its own quiet story.

One of the striking features of this place is how it handles history. It doesn't gloss over it or try to romanticise it. It presents its clutter, its decay, even its eccentricities—like the immense and somewhat unsettling collection of taxidermy—as a reflection of the family who lived here and the values of their time. These things aren’t polished; they’re preserved, imperfections and all. And in black and white, those imperfections gain a kind of dignity. Stripped of colour, the textures, shapes, and patina of age take centre stage. The monochrome palette suits Calke perfectly—it mirrors the faded grandeur, the half-remembered stories, and the slow passage of time.

Throughout the house, small rooms offer moments of quiet contemplation. Stand by almost any window and you’ll find yourself drawn into a scene—light falling just so on a piece of forgotten furniture, or dust dancing in the air above an object left undisturbed for decades. Upstairs, the sense of disrepair is more pronounced. Some rooms are little more than storage spaces for a lifetime’s accumulation of belongings. Others are eerily sparse, inhabited only by shadows and silence.

This series of black and white photographs is a meditation on impermanence. It seeks not to document the house in any literal or historical sense, but to interpret its atmosphere, to trace its textures, and to distil something of its quiet melancholy. Calke Abbey is a place where time has not so much stopped, but slowed—where the past seeps into the present and where decay is, paradoxically, a kind of preservation.