The seed for this project was planted by a line of poetry—quiet, unassuming, yet lingering long after it’s read. In the second canto of The Lay of the Last Minstrel, Sir Walter Scott writes of the “pale moonlight” that filters through aged stone, illuminating the sacred spaces of a past not entirely lost. Those words struck me not only for their poetic elegance but for their resonance with something deeply visual: the way light interacts with ruin, with time, with memory.

Scott himself was no stranger to these scenes. He lived at nearby Abbotsford and chose Dryburgh Abbey as his final resting place. He would have walked among these same arches and cloisters, watched the same shafts of light stretch across sandstone walls softened by centuries of weather, neglect, and reverence. It’s easy to see how the Abbeys of the Scottish Borders might have stirred something in him—they certainly did in me.

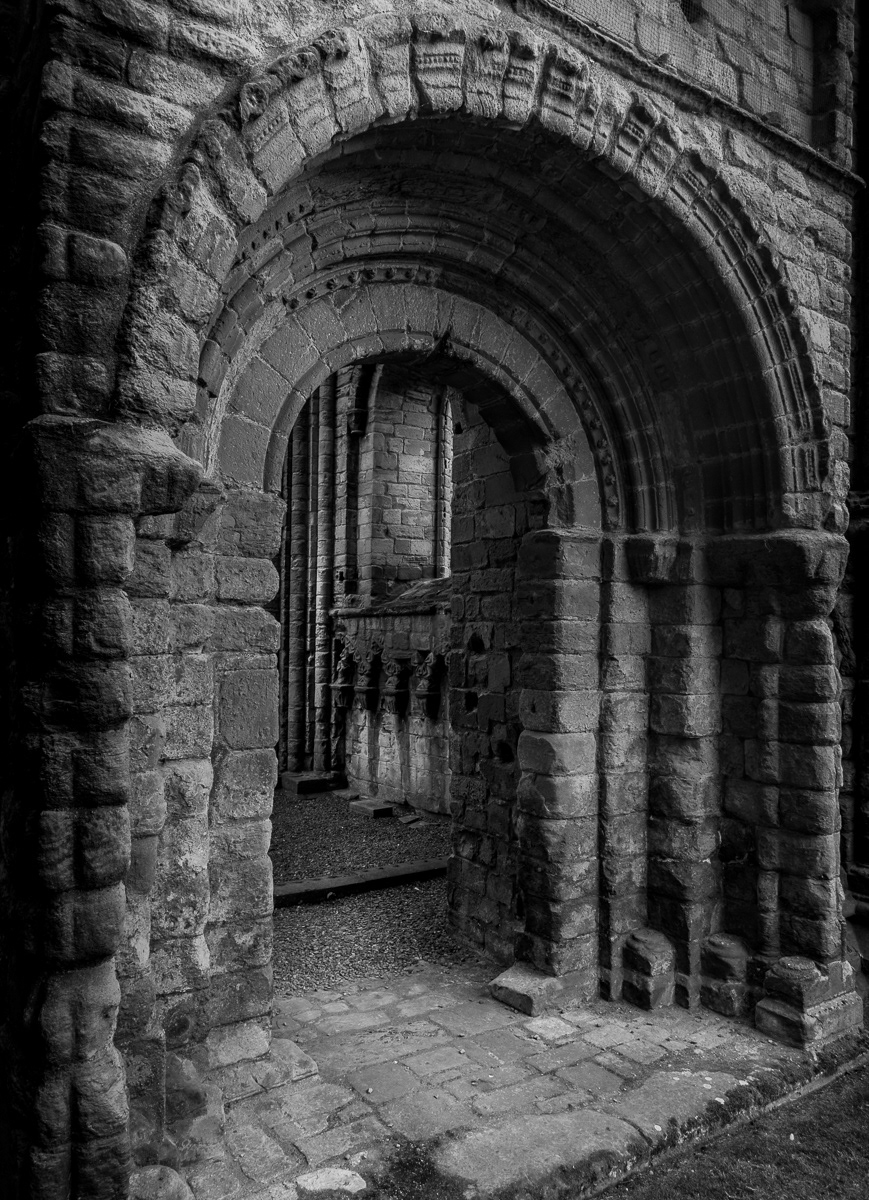

Though I’d visited the Borders before, it wasn’t until two trips in the summer and early autumn of 2019 that I allowed myself to truly see these places. Slowing down was essential. Walking, not just observing. Listening, not just looking. That act of taking time—noticing how light pooled in a broken window arch or the way ivy traced the outlines of forgotten chapels—made all the difference.

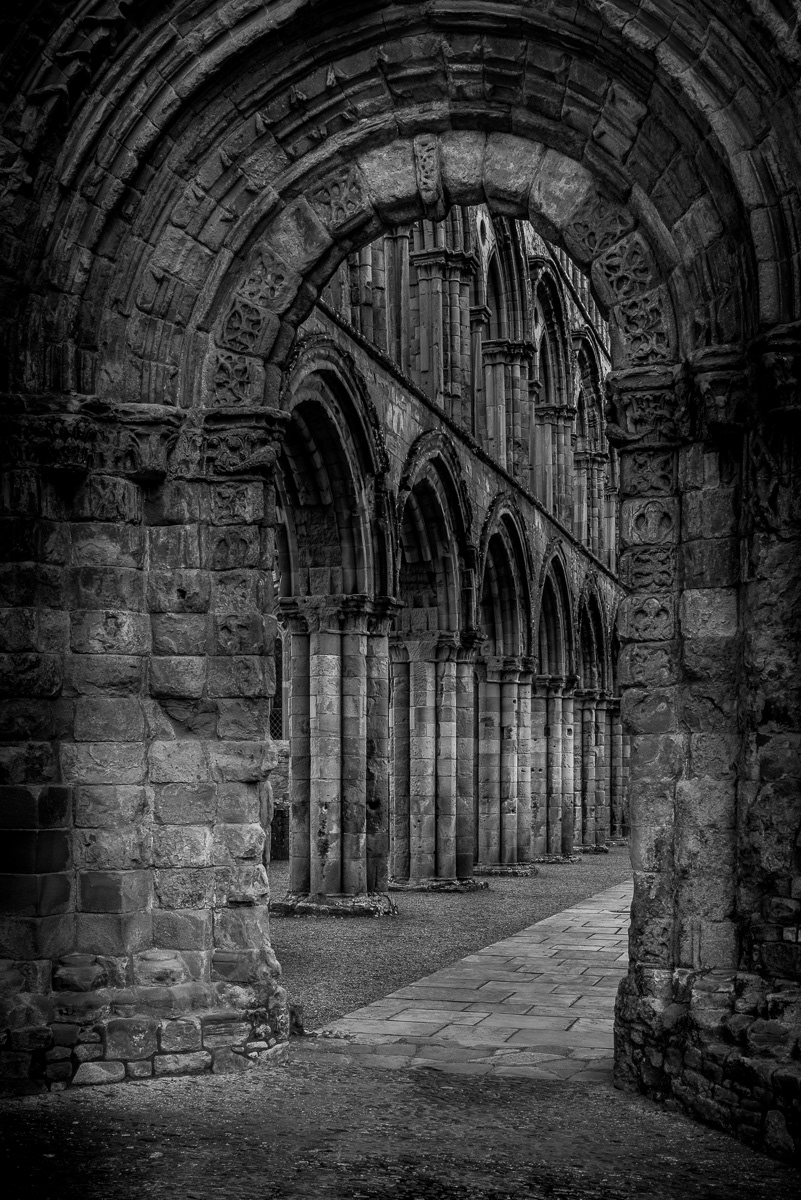

One moment in particular remains vivid. At Melrose Abbey, I stepped from the Aisle Chapels into the Monks Choir just as soft Gregorian chant drifted through the air. Hidden speakers—thoughtfully installed by Historic Scotland—breathed a sense of presence into the ruins. That interplay of sound and stone, echo and silence, moved me more than I expected. The scale of the architecture, the grandeur of its intention, and the ghost of ritual that still seemed to linger—it was a reminder that these spaces were once filled with lives, voices, and purpose.

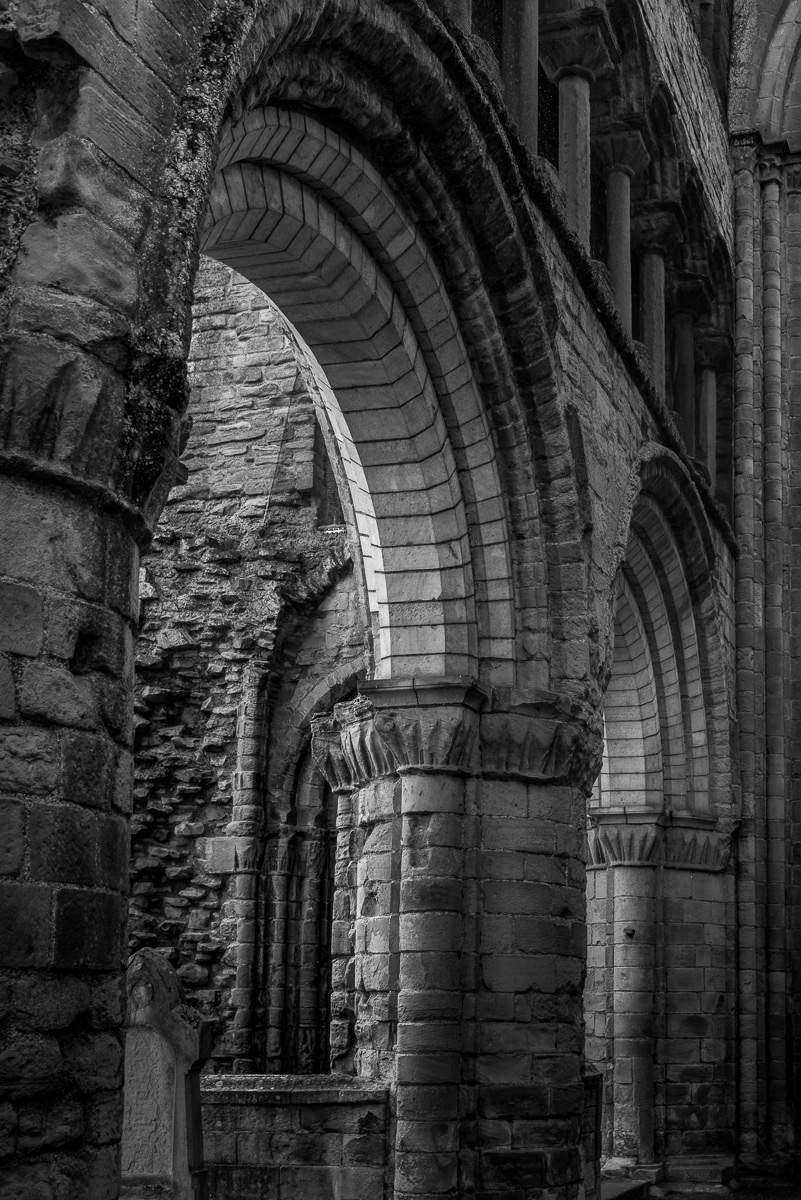

Founded largely under the rule of David I in the 12th century, the great Abbeys of the Borders—Melrose, Dryburgh, Jedburgh, and Kelso among them—stood not only as centres of faith but of political power and learning. Their histories are written in stone: in the elegance of a ribbed vault, in the scars of battle, in the gaps where walls once stood. These places have endured war, desecration under Henry VIII, and the seismic shift of the Reformation. Yet through it all, they remain—dignified in their decay, silent but never mute.

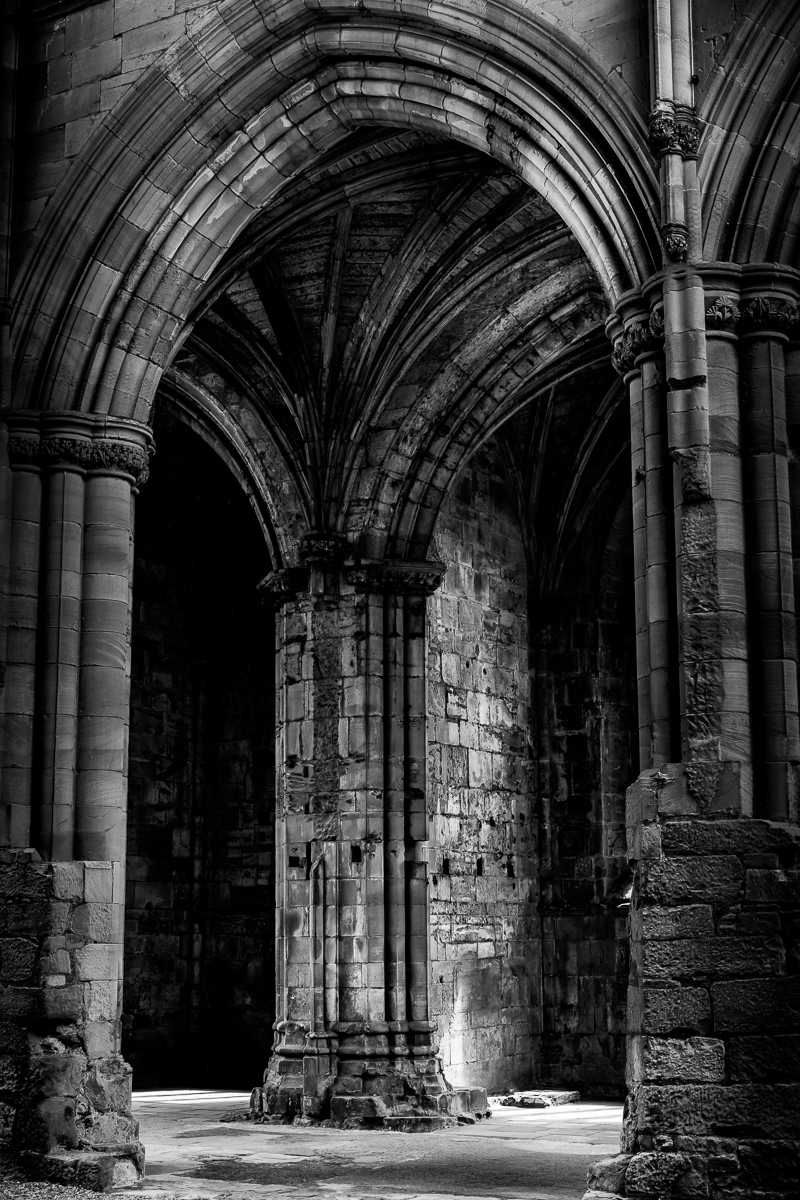

This series of black and white photographs is not a documentary record, nor a historical catalogue. It is instead a personal meditation on light, form, and memory. Black and white seemed the only fitting choice—removing the distractions of colour to let texture, tone, and shadow take precedence. I was drawn to the way light moves across these ruins: sometimes softly, like a whisper; sometimes dramatically, like a final chorus. In each image, I sought to reveal the delicate balance of what remains and what has been lost.

There is beauty in the broken. These Abbeys, even in ruin, still hold a profound grace. They ask us to look closely, to listen deeply. To acknowledge the silence not as absence, but as presence of another kind.

In the end, this project became about more than stone and history. It became about the enduring dialogue between light and time, between architecture and atmosphere. About how places remember—even when their voices have long faded.

.