In the early 1840s, William Henry Fox Talbot wrote to his friend, the astronomer Sir John Herschel, requesting spare flower bulbs to assist with what he called "photographic drawing"—an experimental process he believed might prove useful to botanists. Herschel, with his characteristically poetic touch, coined a word that would come to define a medium: photography.

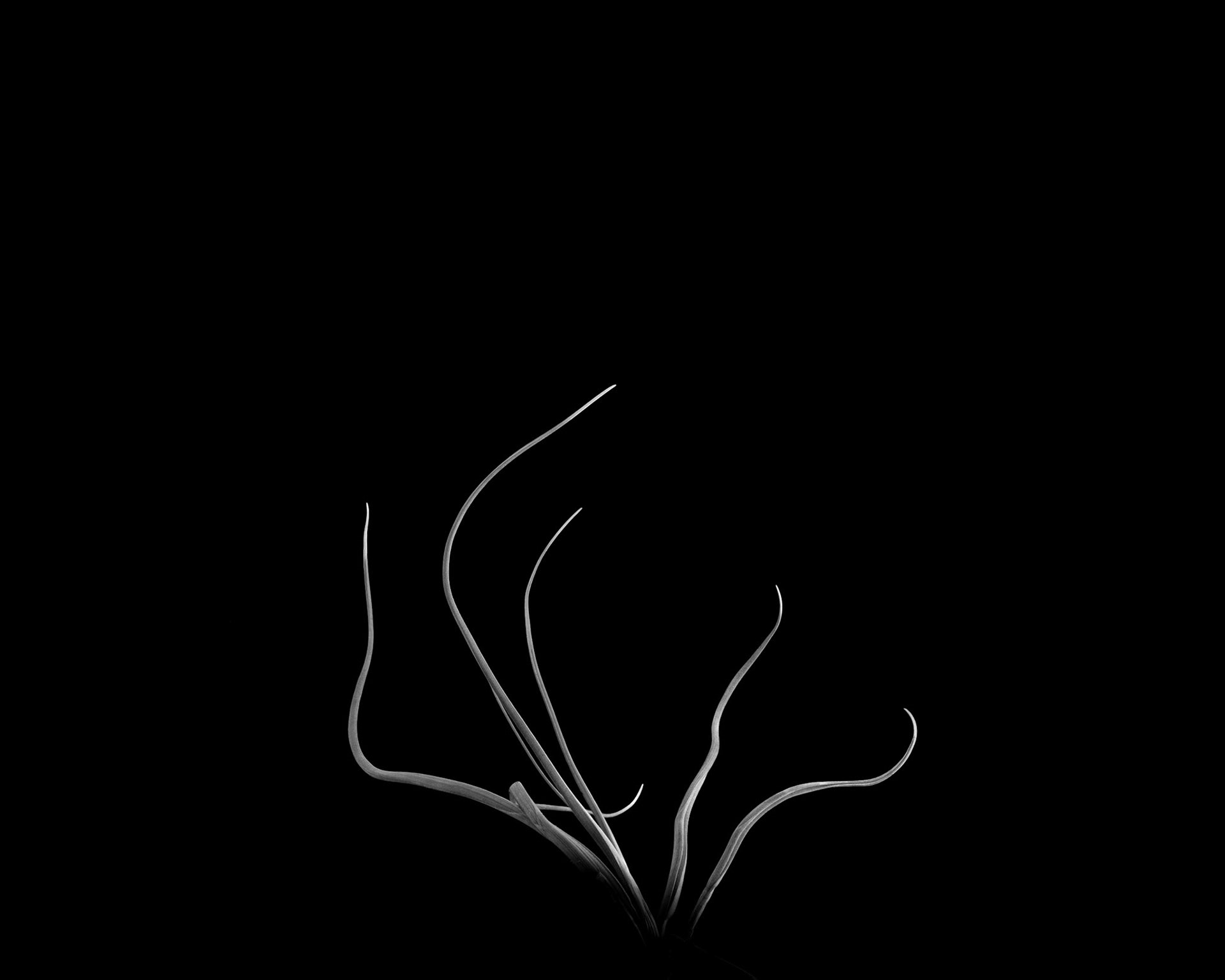

Nearly two centuries later, the botanical subject remains as compelling as ever, though the tools and intentions may have evolved. This series of twelve black and white images—part of an ongoing exploration begun in 2019—continues in that tradition of studying plants through the lens of light. The focus here is on Tillandsia, commonly known as air plants, a remarkable genus within the bromeliad family.

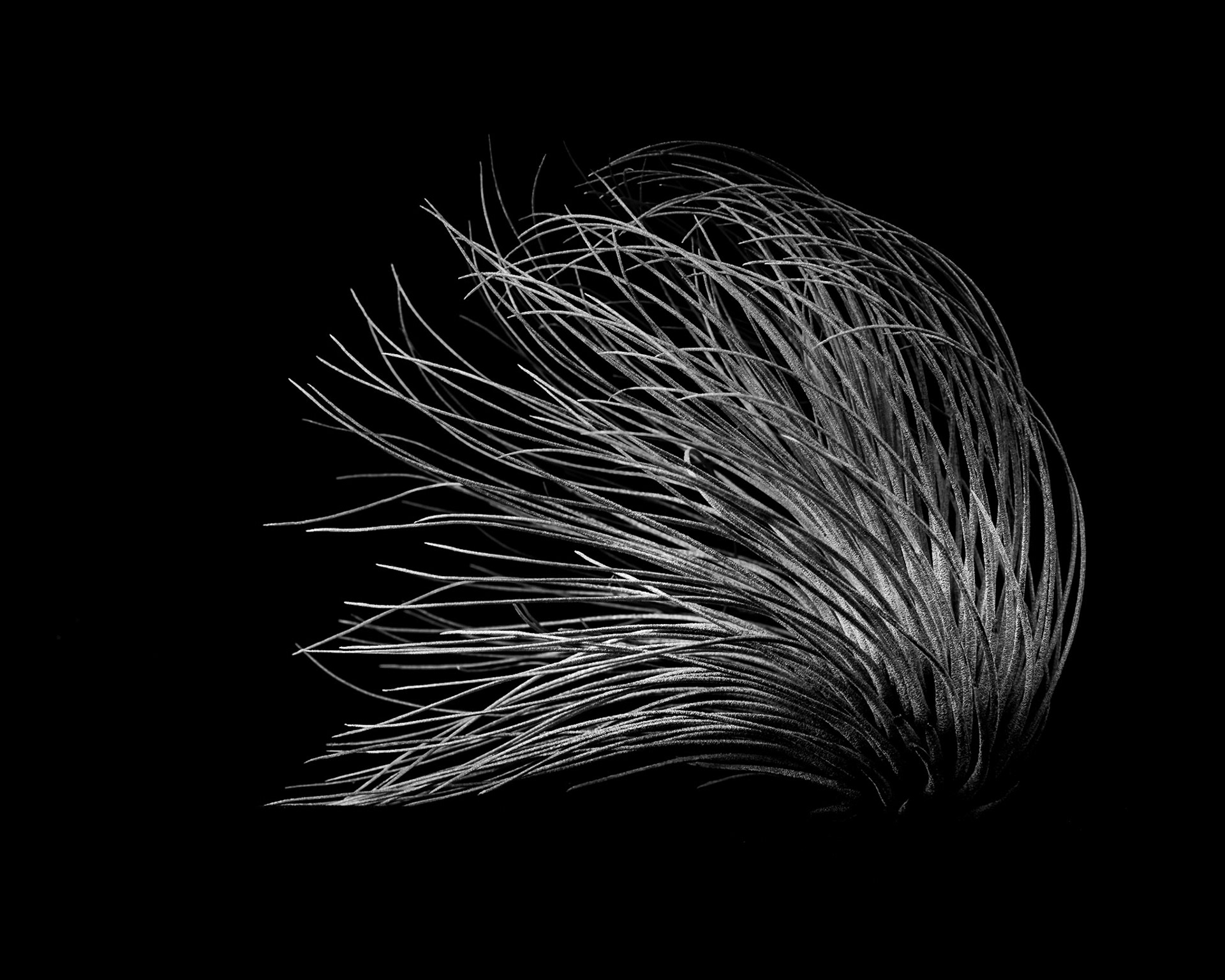

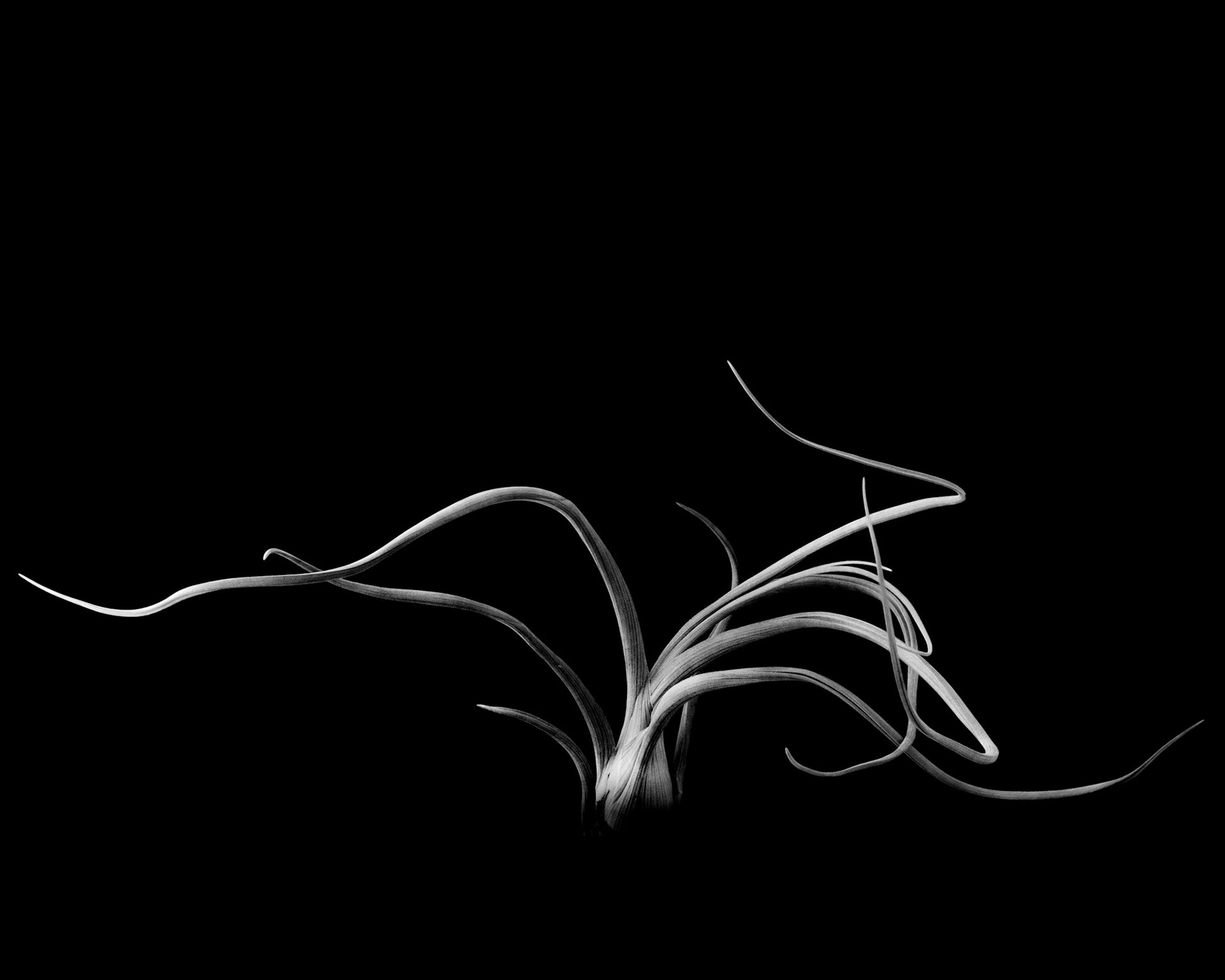

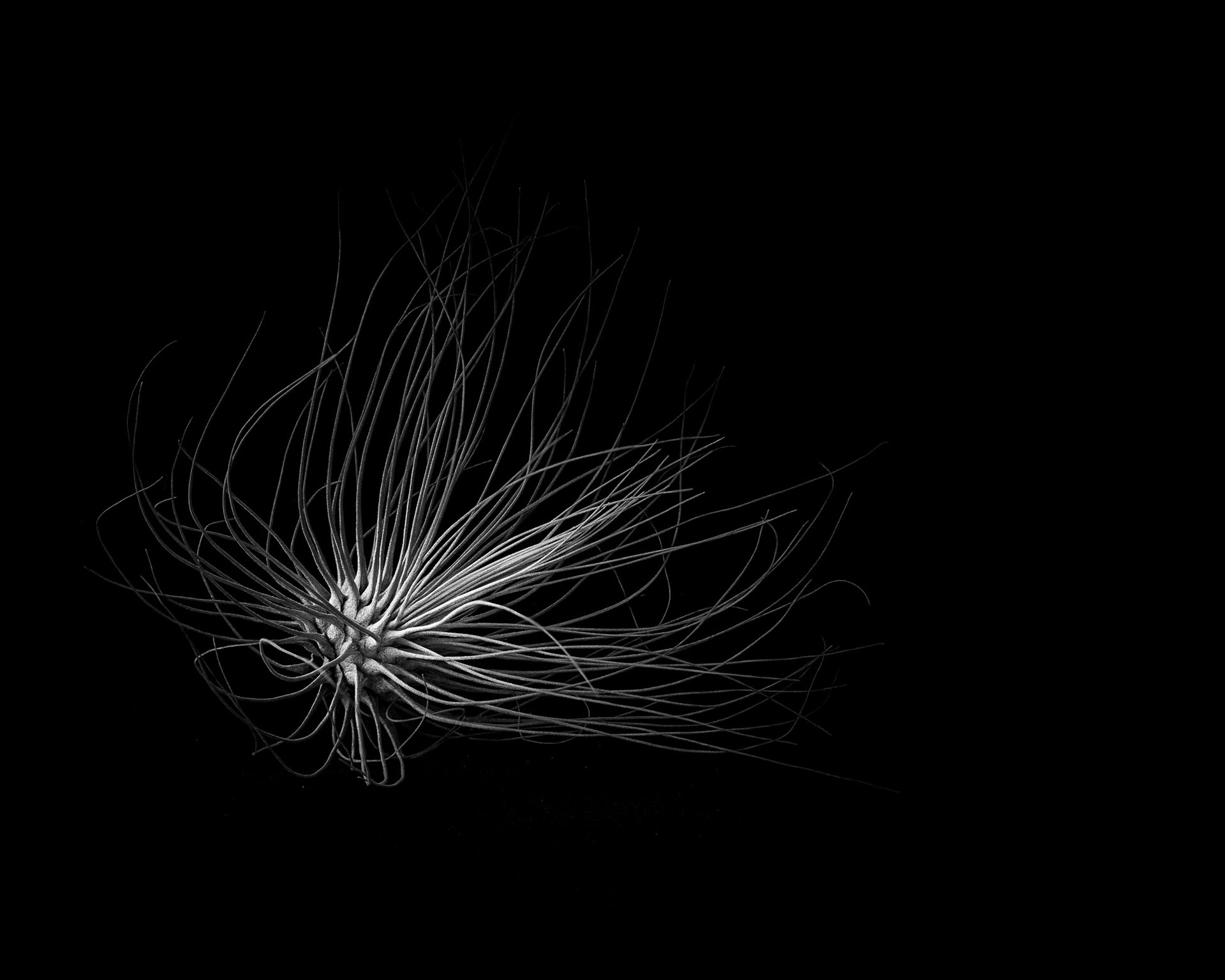

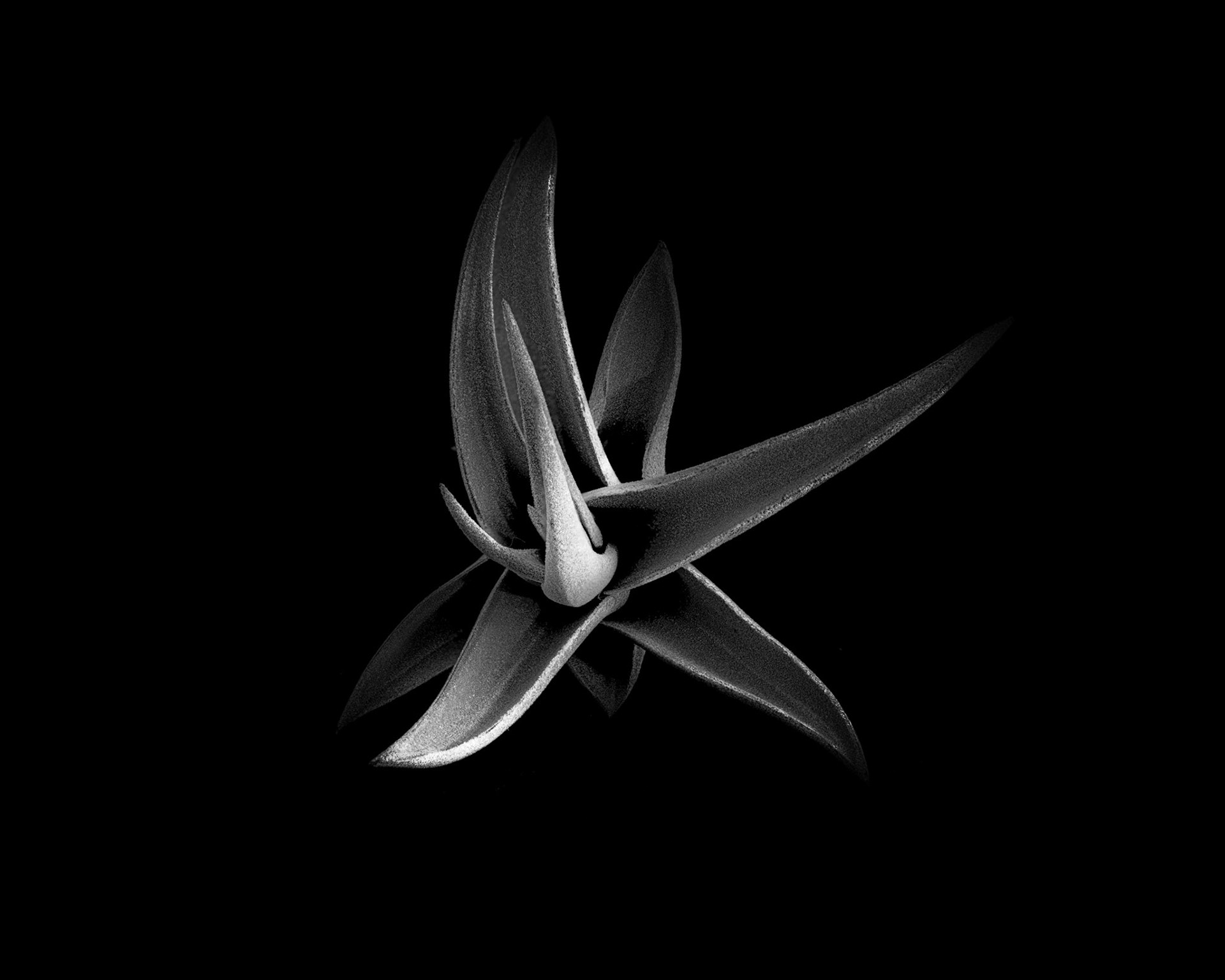

What fascinates me about Tillandsia is their sculptural quality—their sheer diversity of form, texture, and scale. Untethered from soil, they cling to life in the air, absorbing water and nutrients through their leaves. Many species are covered in trichomes, tiny modified cells that help capture moisture from the atmosphere. These same structures give the plants an ethereal, silvery sheen, which reacts to light in subtle and endlessly varied ways.

Working in black and white removes the immediate allure of colour, encouraging a different kind of observation. Without the distraction of green or silver, blush or bloom, the viewer is drawn instead to tone, contrast, and form. Light becomes the true subject, and the plants its medium. In these images, I aim to isolate individual specimens in a way that feels both intimate and abstract—inviting a quiet contemplation of their architecture, and the delicate interplay of shadow and illumination.

Minimalism plays a key role in this work. By stripping away background clutter and presenting the plants against a dark grounds, their inherent elegance comes forward. The curves of a leaf, the tension of a twist, the symmetry (or deliberate asymmetry) of their structure—each becomes a gesture, a mark made in light. There is a meditative quality to photographing these plants. They do not demand attention but reward it. Each one reflects light slightly differently, and so the possibilities for discovery are almost infinite.

Fox Talbot saw in photography a tool to aid science, a way to fix nature on the page. But photography, at its best, has also always been a means of seeing more deeply—of noticing what might otherwise pass us by. These twelve images are not a catalogue of species or an attempt at botanical documentation. Rather, they are a quiet homage to the beauty of natural form, to the poetry of light, and to the enduring legacy of those who first dreamed of drawing with it.